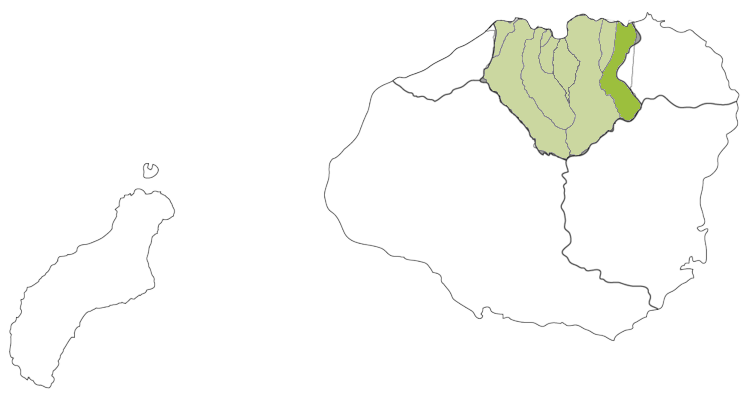

Kalihiwai is the fourth largest of the Halele`a district, measuring 22.3 square kilometers and containing 8600 acres. Kalihiwai means The seaward edge.

Kalihiwai: The seaward edge

The water's edge

Kalihiwai is the fourth largest of the Halele`a district, measuring 22.3 square kilometers and containing 8600 acres.

The shallow valley opening onto the sea contains all the lo`i. The valley is marked by steep cliffs whose names become important in orienting oneself.

No legends, folk tales, or anecdotes of Kalihiwai have been written down.

The earliest mention of the ahupua`a occurs in 1809. Kamehameha of Hawai`i, having attempted to invade Kauaīi twice and failing both times, decided that diplomacy would gain him the island. He sent a chief named Kīhei as his envoy to Ka-umu-ali`i, ruler of Kaua`i. Ka-umu-ali`i showered so many gifts on Kīhei that Kīhei decided to remain on Kaua`i and not return to Kamehameha who would be angry that he had failed to convince Ka-umu-ali`i to cede his island. As a further reward, Ka-umu-ali`i gave Kīhei a wife and made him permanent konohiki chief of Kalihiwai. Kīhei built a heiau to commemorate his good fortune. After he died, the floor of the heiau was dug up and Kīhei, ceremonially laid out in his canoe, was buried there.

Kīhei’s wife, Kekaululu, claimed a houselot and three taro lo`i in the Great Mahele of 1848.

In 1848, 23 inhabitants claimed land but 21 did not, so almost half the population farming the land did not make claims. Of the 23 who did, four left Kalihiwai, returning their land to the konohiki chief and thus forfeiting any rights to claim the land.

In the Mahele of 1848, William Charles Lunalilo, who became King Kamehameha IV, claimed all the lands except those parcels actually awarded to the inhabitants. He was 13 years old at the time.

Orange trees and noni (Morinda citrifolia) were known crops in 1848. By 1850, the depredations caused by hogs and cattle that had gone wild were already noticeable.

Two of Kalihiwai's place names are extensively used in the ancient mele as poetic symbols. Kai-apu literally translates as "sea that snatches with its teeth" and so may refer to the tsunami which from time to time washes over the entire cultivated area of the valley. Figuratively, kaiapu means "to destroy, ravage, or ruin." Lele-iwi, which either means "flying bones" or "bone altar", stood as a symbol of the disasters caused by great anger. A leleiwi was where a body was exposed until such time as the bones could be recovered for burial.