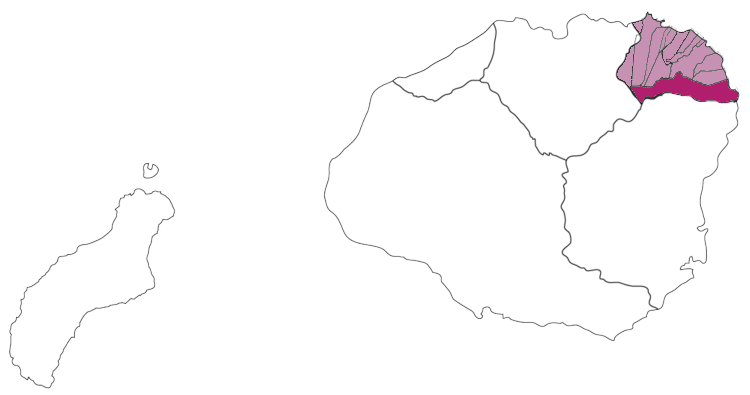

Anahola was a mo`o, a lizard kupua or demi-god, who appeared on land as a man and in the sea as a merman, who lived in this ahupua`a of the Ko`olau district. Like all ahupua`a it was designed to include the deep sea fishing grounds, the reef, shoreline, a river or other sources of constant water, land capable of being irrigated, other land for dry or non-irrigated farming, and the uplands and mountain forests where plants and feathers could be gathered. Anahola is the eastern-most ahupua`a of Ko`olau, abutting the Puna district and the ahupua`a of Kamalomalo`o. On the west, it abuts `Ali-omanu. Anahola’s boundaries on the sea stretch from Papaloa on the east to Kuaehu on the west. The sand dunes were used for burials. The upper part of Anahola valley had taro terraces but the valley sides are too steep to be cultivated.

Anahola contains 6327 acres of land. It is watered by the Anahola river which rises in the mountains overlooking Kalihiwai and Keālia. It is fed by many tributaries, the four most important being Pe`e-kō-`apu (Hidden medicine made of sugar cane), Ka-ū-pākū (The veiled breast), Ka-ālula (A special variety of lobelia flower), and Ke-ao-ōpū (The rising dawn).

The land itself was divided into land units called `ili, which were of different sizes and shapes. The `ili was divided into smaller land units called mo`o, and within those mo`o were either lo`i (irrigated pond fields) where taro was grown, or mala (dry fields) where plants like yams and sweet potatoes were grown.

Houses were in areas that were not well suited for agriculture. The Hawaiians did not waste good land.

The maka`āinana (commoners) had to spend one day in every ten tending to the lands of the konohiki (local chief). These lands were called kō`ele. The konohiki was responsible to his chief for providing food of all sorts in addition to the goods, such as tapa and gourd containers, produced in the ahupua`a.

Anahola in 1850

In 1848 King Kamehameha III agreed to divide the lands of Hawaii three ways. One third of the land was to belong to the men and women who actually lived on it and farmed it, the maka’āinana. These people not only earned their living from the land but their labor and products had for generations also provided for the chiefs and priestly class.The maka’āinana were invited to write to the Land Commissioners in Honolulu, stating their claim for the land they lived on. From the descriptions given that day, it is possible to form a dim picture of land usage of Anahola as practiced in 1850.

One man wrote on January 13, 1848:

The Land Commissioners, Greetings: I hereby state my claims at Anahola. There are three lo’i and the pali wauke, named Piwaho, and the house lot. Those are my claims. With aloha, Paia. (No. 4627)

Two years later Commissioners for Kaua’i were appointed. On February 5, 1850, the Commissioners for Ko’olau, Halele’a, and Nāpali districts, Reverend Edward Johnson and Kaehu sat down to a desk, with pen, ink, and journal in front of them. Claimant Paia appeared before them and they listened silently as his two witnesses agreed that they knew his land. This land was described and its boundaries given, and entered into the journal:

Kuohu sworn he has seen Paia’s land in Anahola.

Section 1 - House lot at Pukalio

Mauka Konohiki pasture

Hanalei Road

Makai Naelele’s pa

Puna Konohiki pasture

Section 2 - 2 lo’i and a pasture, Kepohe

Mauka Konohiki pasture

Hanalei Hao’s loi

Makai Konohiki pasture

Puna Konohiki pasture

(This) land from Naelele to Paia, his young brother, in 1844, because he had come there from Waipa. No other claimant for this land, no objections. Anahola sworn he was seen Paia’s land in the same way as Kuohu secured.

Anahola was the name of a man. He also claimed land that day.

Sixty seven claims were made in this ahupua’a. This did not include the konohiki’s claim to all the land not otherwise claimed, water rights, reef and deep sea fishing rights, as well as the rights to the feathers of the mountain birds.

321 lo‘i were claimed in 1850. There were many more, for some people did not claim the land they worked, and none of the konohiki’s lo’i are listed, for the chief took for himself all the other lands no one else claimed. This large number of claims nonetheless implies a large population, for an acre of taro land was able to furnish food for 20 to 30 people a year.

In addition to the mo‘o lo‘i, there were loko `o‘opu, fishponds where the goby fish was raised, The ‘o‘opu, Chronophorus stamineus, ate the rich growth of algae that grew in the ponds, algae fed by the flow of water coming through the lo’i above. It has ben estimated that 10,000 pounds of algae would create 1000 pounds of a herbivorous fish like the ‘o‘opu and that 1000 pounds of ‘o‘opu would create 100 pounds of mankind. This means that these agricultural pond fields supplied the men and women their necessary protein one hundred times more efficiently than the natural food chain did.

The loko ‘o‘opu was a grazing area in which the farmer cultivated algae for his fish, just like a rancher raises grass to feed his cattle. The value of his algae was recognized, for there is a land area in the rich bottom lands called Palawai (Pond scum).

Wild ‘o‘opu were caught in the streams and certain families had the right to erect a dam across a stream. This dam was made up of long bamboo sticks laid side by side and lashed together. The water flowed between the sticks but the fish could not pass and the fisherfolk could catch them by hand.

The non-irrigated land suitable for dry-land farming was called kula. An individual field was called a mala and if it grew only grass, it was called a kula weuweu. A smaller field was called a kuakua.

In 1850, there were 93 mala of noni, the Indian mulberry, Morinda citrifolia. This plant belongs to the same family as gardenia and coffee. It bears large, conspicuous leaves and fruits that look like small, misshapen breadfruit. The fruit is whitish yellow, unpleasant to taste and smells no better. It is one of the plants that the first Polynesians brought with them when they settled Hawaii. The bark yielded a red dye, the root a yellow dye. In times of famine, the fruit could be eaten.

The noni fruit was used to make a poultice which was applied to broken bones, especially compound fractures when the skin was broken. Fruit at different stages of growth, from the small forming stage to the overripe stage were mashed and heated. This paste was applied to the wound and wrapped with ti leaves. It was also useful for healing sprains and drawing boils.

The second most important kula crop of Anahola was wauke, the paper mulberry, Broussonetia papyrifera. It, too, had been brought to Hawaii by the earliest settlers. It has heart shaped leaves and male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. The bark was beaten into tapa which in turn was made into clothing and bedding, for it is long lasting, washable, and warm.

Tapa making is a long process. The bark must be scraped, soaked, beaten, dyed, washed, sun-bleached, and perfumed. The narrow strips of soaked bark were beaten together on an anvil with carved beaters. The sound of tapa beaters must have echoed constantly from the surrounding cliffs. There were still 66 mala of wauke in Anahola in 1850, although more and more people preferred to wear western clothing, since they lasted longer and did not need the intense labor to produce.

In addition, there were still 6 mala of bitter gourd being grown. These plants yielded small gourds which could be turned into water or food containers. Large gourds were used as storage cases for clothing, feather work, or fishing equipment.

Recently introduced plants are also noted in the claims. 22 orange trees are listed. The official account of Captain Vancouver’s voyages states that at the time of the March 1792 visit he gave garden seeds and "orange and lemon plants that were in a flourishing state". Archibald Menzies, who was the botanist for this expedition, said "…and to further to these industrious people’s collection, upwards of a hundred young orange plants were sent on shore before our departure … to be planted in different places through the island."

By 1850 There had been an attempt to grow oranges commercially at Hanalei, a venture succeeded until about this time when a blight hit the plants.

There were also two mala of a new crop, coffee, another plant that was being tested for its commercial possibilities.

Three other species of trees with useful qualities were mentioned in the claims. Only one claimant thought his hala trees worth mentioning, even though they were common everywhere. Mats are woven from the leaves and the fruit was strung into lei.

There were some breadfruit trees, a useful addition to the diet but they only fruited in the early summer months.

Six kou trees are listed. Kou, Cordia subcordate, was used for making bowls. The wood was soft and easy to carve, yet long lasting and did not crack the way harder woods do as they dry.